September.

The beginning of fall, the last breaths of summer, and pool shutdowns.

Over the past two weeks, my two local 50m pools both took down their respective backstroke flags and closed up shop for annual maintenance shutdowns.

Which left only a cramped, hot, dark, 2ish lane YMCA pool available for lap swimming.

Training there is usually a dice-roll when all the area pools are open.

But when all the other pools are closed?

A chlorinated and free-range gong-show. It didn’t take much to imagine how many times I’d get kicked in the side, arms and side of the face from six-foot wide whip kicks.

My first thoughts were this: “Maybe I should take some time off; after all, how can I expect to train in a bustling lane with lap swimmers varying from fast masters swimmers to floating, head-up breaststrokers? If only the other pools were still open I would really train hard this week.”

My second thought, shortly after, was this: “No excuses, I can still go and do kick or vertical kicking.”

(In case you were curious: I racked up a solid 12 hours of assorted vertical kicking over the span of that two weeks. My underwater dolphin kick has never felt so good.)

It’s funny how when things aren’t ideal or perfect we slide into the warm and comfortable embrace of a good excuse.

The moment a loophole or an exception shows up, we dive through it head-first like it’s a hula hoop floating in the water (great drill for developing a clean entry on your dive, by the way).

You already have what you need.

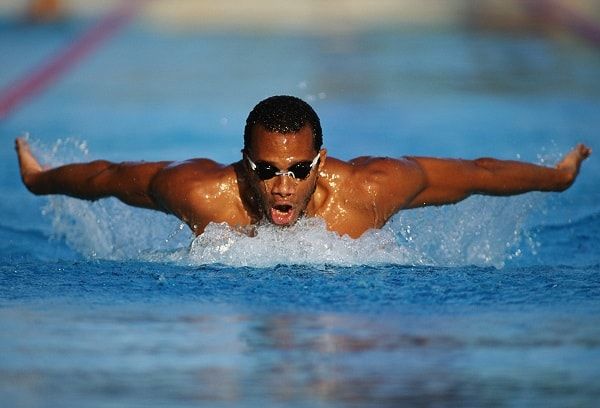

At the 1988 Olympics, in Seoul, South Korea, American superstar Matt Biondi was expected to challenge Mark Spitz’ standard of 7 gold medals at a single Olympics. (Yup, Phelps wasn’t the first to take a swing at that record.)

In the 100m butterfly, Biondi was cruising to what looked like a certain gold medal, half a body length ahead of the field which included butterfly heavyweights Michael Gross (Germany), Jon Sieben (Australia), Andy Jameson (GBR), and a 19-year old from a country most of the world couldn’t find on a map, Anthony Nesty of Suriname.

As the finish bore down, Biondi faced the timeless quandary for a swimmer coming into the finish of a race: finish on a glide or finish on a half stroke?

He went with the former, gliding into the finish from about 2m out from the wall, stretching out his 6’8” frame.

Nesty, two lanes up, charged all the way to the finish, closing on a full stroke and out-touching the favored American by 1/100th of a second, 53.00 to 53.01.

Suriname, at the time of Nesty’s Olympic victory, had ten swimming pools.

One…zero. Ten.

In the whole country.

Look…

Circumstances will never be perfect.

The lane will always be too busy. You will never absolutely feel like working hard. Your training facilities will never be the best.

There will always be someone more talented, more tall, more gifted, more whatever.

But you can choose to be the hardest worker in the pool.

Conditions have nothing to do with your effort.

Do work with what you have.

More Stuff Like This:

This Mental Training Book for Swimmers Will Help You Swim Like a Rock Star This Season. Ready to take your swimming to the next level? This complete guide to a high-performance mindset will help you conquer your goals, practice, and the competition.

Olympian Mike Burton and the Fast 66: How Hard Work Redefines What is Possible. Swimmers are prisoners of what they think is possible. Here’s a lesson in how hard work in the pool helps you to redefine what you are capable of in the water.